I continued working through the Neural Networks book. A lot of the rusty math started finally coming back to me in sudden bursts of insight, and the book broke the main formulas down enough that I was able to really follow what was going on and how the pieces were working together on a conceptual and mathematical level.

I got some Python code running in the terminal to create and backpropagate a neural network for classifying handwritten digits, using the MNIST dataset, following along with the exercises in the book. It’s pretty exciting how quickly the error decreases with the stochastic gradient descent optimization on the weights and biases of the neural network nodes. It seems to learn very quickly!

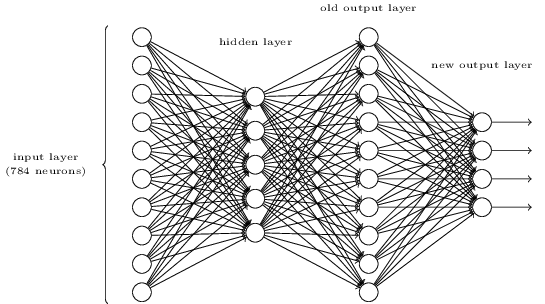

I was bummed to learn that deep neural networks, which have multiple hidden layers between the input and output nodes, are apparently much harder to train than these “shallow” neural networks with just one hidden layer. Deeper networks are awesome because they can make much smarter decisions and much more complicated distinctions and abstractions between things by looking at patterns in a more complicated way. There is apparently some very recent math (from 2006!) that enables more efficient learning in deeper neural nets, that can train networks with 5 to 10 hidden layers. I’m looking forward to learning how to implement these deeper networks, but will have to find a new source of learning materials as this book is currently unfinished and stops after explaining the mathematical proof and conceptual model behind back propagation.

What is cool about the limitations of training deep neural networks is that one of my early ideas for a Hacker School project now seems like it would actually be useful, more than when I mistakenly believed that many-layered neural networks were easy to set up and train. I wanted to make a modular neural network for image classification, with input layers that took particular sets of images and output them into different categories. For example, networks that detect lines, or shapes, or an eye, or sort by color, etc. The neural networks could be set up in such a way that they are trained individually, but they could be linked to feed information from one to the next in order to do more complicated classifications. Training neural networks takes some processing power, but once they are well-trained, they can process and classify new data very quickly, even running in the browser. I think it would be a really cool open-source project if I could set up a modular framework so that people could add different types of pre-trained visual image processing neural networks that could then be linked up in a custom way for anyone who needed to do image classification quickly.

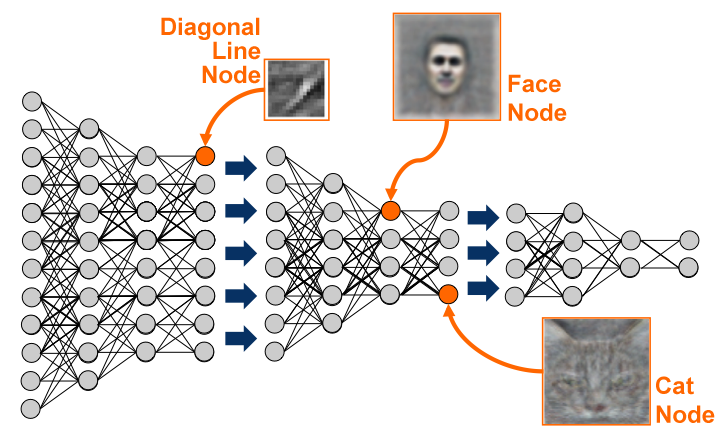

I discovered another article about shallow neural networks and handwritten digit classification that was very exciting! I hadn’t realized until I read it that once the neural network is trained, you could display the relative weights of the inputs to each hidden neuron as a representation of what that hidden neuron was looking for. This is a very similar concept to the discovery of independent features in Non-Negative Matrix Factorization that I learned about last week. The “features”, or the features the hidden nodes represent, can be represented and described purely by the relative weights of the data inputs they represent. For the articles and topic themes in the Non-Negative Matrix Factorization exercise, that would be the words that describe the theme. For handwritten digit classification, that turns out to be the intensity of the weight of each pixel input for that node, which can be represented visually.

You can actually see what visual features of the image a particular hidden node of the digit classifier neural network is looking for, and it’s easy to imagine that if two hidden nodes were highly active, it could represent for example a top curve and a bottom curve that would indicate the number zero. This visualization of the input weights helped a lot with my conceptual understanding of what the hidden nodes represent and how they might be working together.

This got me very excited about the idea of applying a neural network classifier to my beer ratings dataset of 200,000 beer ratings from a few thousand users of a couple thousand beers. I realized that not only can I use a neural network to recommend beers to users very quickly once the network is trained, but I realized that for beers, the hidden nodes would represent groupings of beers into a sort of taste profile. I’m imagining a node each for hoppy-bitter beers, boozy belgians, roasty stouts, and sweeter lighter beers, with each individual user’s preferences being some combination of those flavor types, represented in the program by different activations of those hidden nodes. This is very exciting!

I got my beer data into an appropriate format and trained a neural network with 10 hidden nodes (which to my understanding represents 10 beer-taste-profiles), and tomorrow I’m going to work on a representation showing which of the top 100 beers activate each node, representing independent features (meaningful beer groupings) of the dataset.