This week I worked on fleshing out my rewrite of BeerChooser, my first iPhone app from 2010. I had written a Beer List module last week, and I realized that I could use several instances of this same module for each of the tabs in my beer app, instead of the similar-but-separate view controllers of my original app. This fits well with my goal of making bug-discouraging, maintainable code using a more modular architecture than is usually used in iOS development.

I realized that the only things that were different in each tab in my beer app were the title, the tab image, and the data source for the list of beers, and that I could create something that would allow me to change only these settings for each instance of the beer list module.

At first, I used an enum for the different tab settings.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

This worked, and took advantage of reusing the module code like I wanted (which eliminates the bugs you can get from having to copy a change over to nearly-identical code in another class), but it was not a very object-oriented programming way of doing things, and it created work and bug-possibilities due to all of the switch statements it needed for managing the different property settings for each enum type.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | |

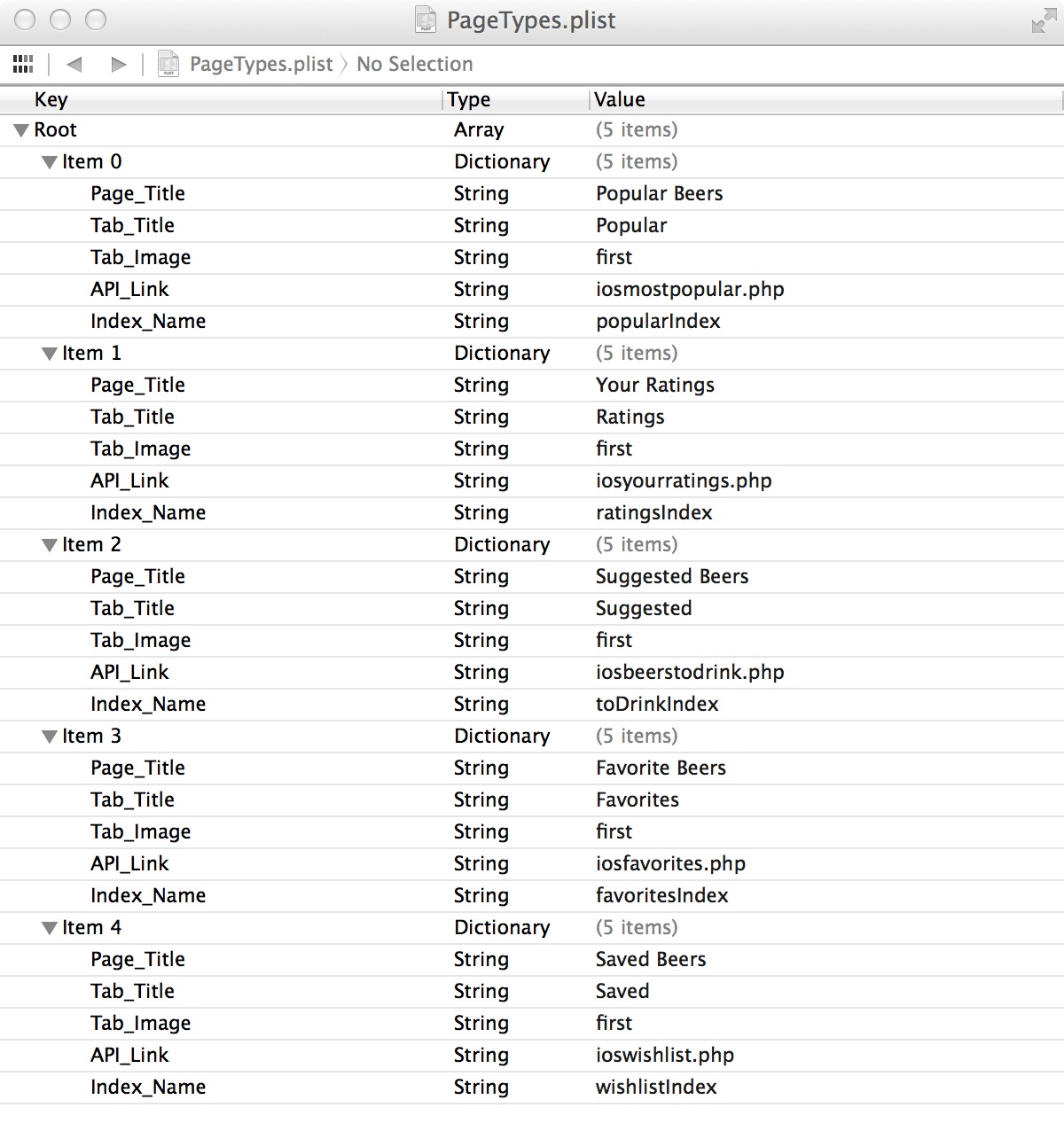

After talking through some of the problems with this solution, I had the idea of using a Property List to define the particulars of each tab, and the loading the .plist into a class and pulling out the dictionary keys of each tab to define the settings for that Beer List module instance.

This greatly simplified the code for defining the properties of a Beer List instance, and makes it incredibly easy to update and maintain, with a low likelihood of introducing bugs through editing page titles. To reorder the tabs, I just drag that tab’s dictionary to a different position in the Property List array, and the tabs reorder themselves to match.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | |

I figured out a sensible way to add a network API manager within the framework of the VIPER software architecture model. In order to keep network separated from the rest of my application code, I created a network API manager in a similar way to the local data store manager.

There’s a base API manager class for the entire application, which is the only class that actually talks to the server and knows that I’m using the AFNetworking framework to manage server requests. This is awesome because if I decide to use another framework, I only have to worry about updating one file. This same file loads in my secret Configuration variables (like my OAuth Client ID and Client Secret, which are cleverly hidden from my public GitHub repository using this technique Mike Walker shared with me), and remembers the base URL of my server. It knows how to send a general POST request to the server, and adds the authentication parameters to the request it’s told to send.

Then, each module has its own API manager that’s in charge of talking to the base API manager, which calls the API link for the instance, and manages saving the beers with the proper index for that instance.

I’ve found that using a more robust, maintainable architecture in my application has slowed down my development a bit, as for each feature I add (such as communicating with an API), I have to stop and think about the smartest way to implement that feature to keep to the goal of modular code with different aspects kept separated. The plus side is that it seems to just work in a way that Massive View Controller-style programming often does not, so some of the initial design time is saved in much less debugging time. Plus, as soon as you need to make a change (to the view layout, to the data store, etc), the time saved by having those aspects of the code in their own isolated files more than makes up for the initial time invested in separating these functions intelligently.

On Friday, I worked with Tom on Google’s Store Credit challenge in Swift.

The problem:

You receive a credit C at a local store and would like to buy two items. You first walk through the store and create a list L of all available items. From this list you would like to buy two items that add up to the entire value of the credit. The solution you provide will consist of the two integers indicating the positions of the items in your list (smaller number first).

We spent a good amount of time figuring out how to use Swift to run in the terminal instead of how it would typically be used in Xcode as a file within an app project target. We were successful with this, and figured out not only how to read in text from a file on the local filesystem and output our answer to another local text file, but were successful in calling a Swift file to run in the terminal.

Running in the terminal:

1

| |

Reading and writing text:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

This is great, because for larger computations like this, Swift Playgrounds will crash, or run so slowly that they never find an answer.

The coding challenge itself was a lot of fun. We created a dictionary that, for each item we found, stored its cost as a key in a dictionary, with the value being an array of each position in the original list of items where the item was found.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

This solved the problem we initially ran into with repeated items being the answer, when we were using a dictionary with the keys being items, and the values being the (single) position where we found that item.

Every time we added a new item to the dictionary, we looked to see if the difference between that item and the store credit had been previously stored in the dictionary. If it was there, then we had our pair of items that we could buy with the store credit.

This was a TON of fun. I especially enjoyed starting off whiteboarding the problem, and discussing how various solutions would change if the constraints of the problem changed slightly, and then moving on to more individual coding solutions to the problem. I’m hoping to spend a lot more time doing fun challenges like this in the coming weeks!